这篇文章会介绍CPython 2.7.12中字符串intern的知识。

首先举一个例子说明内置的intern函数的用法:

>>> s1 = 'foo!'

>>> s2 = 'foo!'

>>> s1 is s2

False

>>> s1 = intern('foo!')

>>> s1

'foo!'

>>> s2 = intern('foo!')

>>> s1 is s2

True

你应该已经体会到了用法,但是,在python内部它是怎么工作的呢?

String Intern(字符串驻留)

PyStringObject结构体

我们需要深入CPython的源码,表示Python字符串的C结构体PyStringObject在stringobject.h文件中:

typedef struct {

PyObject_VAR_HEAD

long ob_shash;

int ob_sstate;

char ob_sval[1];

/* Invariants:

* ob_sval contains space for 'ob_size+1' elements.

* ob_sval[ob_size] == 0.

* ob_shash is the hash of the string or -1 if not computed yet.

* ob_sstate != 0 iff the string object is in stringobject.c's

* 'interned' dictionary; in this case the two references

* from 'interned' to this object are *not counted* in ob_refcnt.

*/

} PyStringObject;

根据注释,如果字符串被interned,变量ob_sstate的值将不再等于0。一般来说,我们不会直接接触这个变量,而是通过下面定义的宏PyString_CHECK_INTERNED来读取它:

#define PyString_CHECK_INTERNED(op) (((PyStringObject *)(op))->ob_sstate)

interned字典

然后,让我们来看stringobject.c。24行定义了一个对象的引用,interned字符串将会存放在这个对象里。

static PyObject *interned;

实际上,这个对象就是一个正常的Python字典,在第4744行被初始化

interned = PyDict_New();

最终,所有的魔法都在第4731行``PyString_InternInPlace函数中发生。下面是函数实现:

PyString_InternInPlace(PyObject **p)

{

register PyStringObject *s = (PyStringObject *)(*p);

PyObject *t;

if (s == NULL || !PyString_Check(s))

Py_FatalError("PyString_InternInPlace: strings only please!");

/* If it's a string subclass, we don't really know what putting

it in the interned dict might do. */

if (!PyString_CheckExact(s))

return;

if (PyString_CHECK_INTERNED(s))

return;

if (interned == NULL) {

interned = PyDict_New();

if (interned == NULL) {

PyErr_Clear(); /* Don't leave an exception */

return;

}

}

t = PyDict_GetItem(interned, (PyObject *)s);

if (t) {

Py_INCREF(t);

Py_DECREF(*p);

*p = t;

return;

}

if (PyDict_SetItem(interned, (PyObject *)s, (PyObject *)s) < 0) {

PyErr_Clear();

return;

}

/* The two references in interned are not counted by refcnt.

The string deallocator will take care of this */

Py_REFCNT(s) -= 2;

PyString_CHECK_INTERNED(s) = SSTATE_INTERNED_MORTAL;

}

可以看到,interned字典中的keys都是指向字符串对象的指针,values也是同样的指针。另外,字符串的派生类不能被intern。不考虑错误检查和引用计数,我们可以用如下伪代码重写这个函数:

interned = None

def intern(string):

if string is None or not type(string) is str:

raise TypeError

if string.is_interned:

return string

if interned is None:

global interned

interned = {}

t = interned.get(string)

if t is not None:

return t

interned[string] = string

string.is_interned = True

return string

简单吧!

字符串intern的好处

共享对象

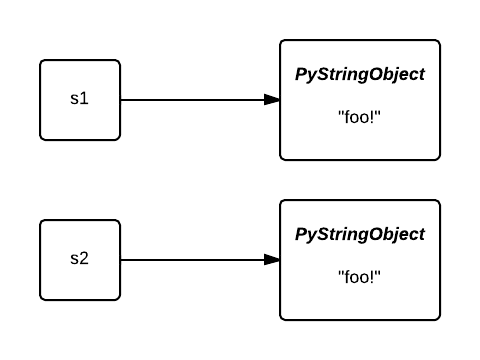

为什么你要使用字符串intern?首先,共享字符串对象可以减少内存占用。让我们回到第一个例子,一开始,变量s1和s2指向两个不同的对象。

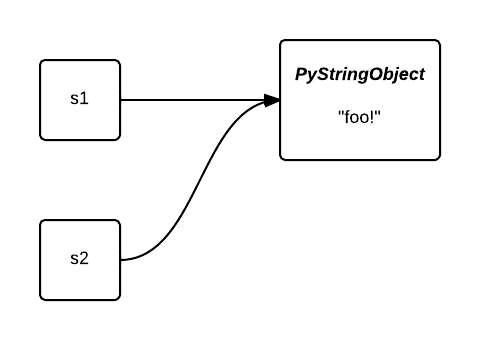

在intern之后,他们都指向了同一个对象。第二个对象占用的内存被节省下来了。

在处理一些低信息熵的大列表的时候,intern非常有用。例如,当我们解析一个语料库,we could benefit from the very heavy-tailed distribution of word frequencies in human languages to intern strings to our advantage。下面的例子中,我们会使用NLTK来导入Hamlet by Shakespeare,使用Heapy来观察intern前后对象的堆栈使用:

import guppy

import nltk

hp = guppy.hpy()

hp.setrelheap()

hamlet = nltk.corpus.shakespeare.words('hamlet.xml')

print hp.heap()

hamlet = [intern(wrd) for wrd in nltk.corpus.shakespeare.words('hamlet.xml')]

print hp.heap()

$ python intern.py

Partition of a set of 31187 objects. Total size = 1725752 bytes.

Index Count % Size % Cumulative % Kind (class / dict of class)

0 31166 100 1394864 81 1394864 81 str

...

Partition of a set of 4555 objects. Total size = 547840 bytes.

Index Count % Size % Cumulative % Kind (class / dict of class)

0 4 0 328224 60 328224 60 list

1 4529 99 215776 39 544000 99 str

...

如你所见,我们极大地减少了字符串对象的数量(从31187减少到4555),并且内存占用减少了6.5倍

指针比较

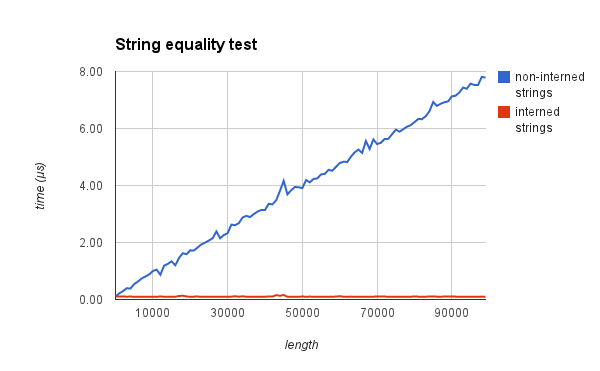

第二,我们可以用O(1)的指针比较来代替O(n)的字节比较

为了验证这个,我测量了在比较两个字符串是否相等的时,intern与否分别的时间。下面的图应该能说服你:

Native interning

在一些条件下,字符串会被原生interning。还是第一个例子,如果我用foo而不是foo!,字符串s1和s2就会被自动地intern。

>>> s1 = 'foo'

>>> s2 = 'foo'

>>> s1 is s2

True

Interned or not interned?

写这篇文章之前,我一直在想,在后台,字符串会根据一个参考字符串长度和构成它们的字符的规则来执行intern。我的想法离正确答案很近,但是,当我操作几组创建方法不同的字符串时,我无法推测出这条规则到底是什么!

>>> 'foo' is 'foo'

True

>>> 'foo!' is 'foo!'

False

>>> 'foo' + 'bar' is 'foobar'

True

>>> ''.join(['f']) is ''.join(['f'])

True

>>> ''.join(['f', 'o', 'o']) is ''.join(['f', 'o', 'o'])

False

>>> 'a' * 20 is 'aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa'

True

>>> 'a' * 21 is 'aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa'

False

>>> 'foooooooooooooooooooooooooooooo' is 'foooooooooooooooooooooooooooooo'

True

在看完这些例子后,你要承认,确实非常难以确定系统是根据什么来执行原生的intern。我们还需要阅读更多的CPython代码来找出答案。

Fact 1: all length 0 and length 1 strings are interned

还是在stringobject.c,我们这些要看PyString_FromStringAndSize和 PyString_FromString函数中都有的一些代码:

/* share short strings */

if (size == 0) {

PyObject *t = (PyObject *)op;

PyString_InternInPlace(&t);

op = (PyStringObject *)t;

nullstring = op;

Py_INCREF(op);

} else if (size == 1 && str != NULL) {

PyObject *t = (PyObject *)op;

PyString_InternInPlace(&t);

非常清晰:所有长度为0和1的字符串都会被intern。

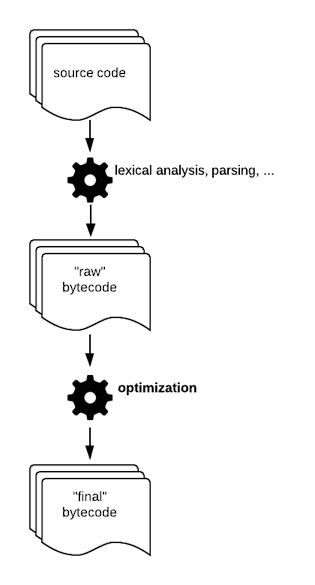

Fact 2: 在编译期间字符串会被interned

你写的Python代码并不是直接被解释器执行,代码会通过一个经典的编译链来生成一种中间语言:bytecode(字节码)。python字节码是被Python解释器这个虚拟机执行的一系类指令。你可以在这里看到所有的指令。通过使用dis模块,你可以看到一个函数或模块执行了哪些指令:

>>> import dis

>>> def foo():

... print 'foo!'

...

>>> dis.dis(foo)

2 0 LOAD_CONST 1 ('foo!')

3 PRINT_ITEM

4 PRINT_NEWLINE

5 LOAD_CONST 0 (None)

8 RETURN_VALUE

正如你知道的,在Python中,一切皆对象。代码也是Python对象,它表示了一块字节码。一个代码对象带有执行时所需要的所有信息:常量,变量名等。我们发现,当在Python中创建代码对象的时候,有一些字符串被intern了:

PyCodeObject *

PyCode_New(int argcount, int nlocals, int stacksize, int flags,

PyObject *code, PyObject *consts, PyObject *names,

PyObject *varnames, PyObject *freevars, PyObject *cellvars,

PyObject *filename, PyObject *name, int firstlineno,

PyObject *lnotab)

...

/* Intern selected string constants */

for (i = PyTuple_Size(consts); --i >= 0; ) {

PyObject *v = PyTuple_GetItem(consts, i);

if (!PyString_Check(v))

continue;

if (!all_name_chars((unsigned char *)PyString_AS_STRING(v)))

continue;

PyString_InternInPlace(&PyTuple_GET_ITEM(consts, i));

}

在codeobject.c中,consts元组包含了在编译期间定义的字面量:布尔值,浮点数,整数和在你的程序中声明的字符串。在这个元祖中存储的字符串,如果没有被all_name_chars函数过滤掉的话,将会被全部intern。

下面的例子中,s1是在编译期间被声明的。相反的是,s2是在运行时产生的:

s1 = 'foo'

s2 = ''.join(['f', 'o', 'o'])

结果是,s1将会被intern,s2不会。

all_name_chars方法将会过滤掉不是由ascii字符,数字和下划线构成的字符串(Python中变量名的命令规范):

#define NAME_CHARS \

"0123456789ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ_abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz"

/* all_name_chars(s): true if all chars in s are valid NAME_CHARS */

static int

all_name_chars(unsigned char *s)

{

static char ok_name_char[256];

static unsigned char *name_chars = (unsigned char *)NAME_CHARS;

if (ok_name_char[*name_chars] == 0) {

unsigned char *p;

for (p = name_chars; *p; p++)

ok_name_char[*p] = 1;

}

while (*s) {

if (ok_name_char[*s++] == 0)

return 0;

}

return 1;

}

理解了这些,我们就知道了为什么'foo!' is 'foo!'等于False,而'foo' is 'foo'等于True,胜利了吗?还没有!

字节码优化产生了更多字符串常量

这听起来和直觉不符,但是在下面的例子中,字符串连接的输出不是在运行时,而是在编译时:

>>> 'foo' + 'bar' is 'foobar'

True

这就是为什么'foo' + 'bar'也被intern了,表达式等于True。

怎么做到的?倒数第二的源码编译器生成了第一个版本的字节码。这个原始的字节码最终会进入最后一个编译器,被称作“窥孔优化”(peephole optimization)

这一步的目标是通过替换更快的指令来产生更加高效的字节码。

常量合并Constant folding

在窥孔优化期间,应用到的一项技术就是常量合并,使用更加简单的常量。想象你是一个编译器,你看到了下面这行:

SECONDS = 24 * 60 * 60

你能做什么来简化这个表达式以在运行时节约几个时钟周期。你可以用计算好的值86400来替换这个表达式。这就是foo' + 'bar'发生的事。让我们定义一个foobar函数,分解相关的字节码:

>>> import dis

>>> def foobar():

... return 'foo' + 'bar'

>>> dis.dis(foobar)

2 0 LOAD_CONST 3 ('foobar')

3 RETURN_VALUE

看到了吧!根本没有看到加法和初始的两个常量'foo'和'bar'。如果CPython字节码没有被优化,那么输出应该是这样的:

>>> dis.dis(foobar)

2 0 LOAD_CONST 1 ('foo')

3 LOAD_CONST 2 ('bar')

6 BINARY_ADD

7 RETURN_VALUE

我们解决为什么下面的表达式正确的问题:

>>> 'a' * 20 is 'aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa'

避免大的 .pyc 文件

那么为什么'a' * 21 is 'aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa'不等于True呢?你还记得在你的包里面会看到的.pyc文件吗。如果一个人写了诸如['foo!'] * 10**9的代码会怎么样呢?这样会导致.pyc文件非常巨大!为了避免这个现象,窥孔优化中产生的序列长度如果大于20,将会被丢弃。

补充

窥孔优化

顾名思义,是一种很局部的优化方式,编译器仅仅在一个基本块或者多个基本块中,针对已经生成的代码,结合CPU自己指令的特点,通过一些认为可能带来性能提升的转换规则,或者通过整体的分析,通过指令转换,提升代码性能。别看这些代码转换很局部,很小,但可能会带来很大的性能提升。

这个窥孔,你可以认为是一个滑动窗口,编译器在实施窥孔优化时,就仅仅分析这个窗口内的指令。每次转换之后,可能还会暴露相邻窗口之间的某些优化机会,所以可以多次调用窥孔优化,尽可能提升性能。

窥孔优化可以在四个方面寻找优化机会:冗余指令删除,包括冗余的load和store指令以及死代码(不会执行的代码);控制流优化;强度削弱;利用特有指令。